Gawai Burong is celebrated to honour the War God - Sengalang Burong. This festival is one of the greatest of all Iban festivals or ceremonies. It was first celebrated by Sera Gunting himself on his return from this grandfather longhouse. The other festivals of bird rituals, by order of importance and expense, includes Gawai Mata’, Enchaboh Arong, Gawai Kenyalang and Gawai Burong, the latter being celebrated in nine ascending stages.

Preparation for the Festival 1. Aum gawai - to discuss preparations for the gawai including fixing dates (nempoh hari), allocation of communal farm (bumai bedandang) where a portion of the harvest is allocated for ceremonial needs and setting time to begin brewing of the rice wine (tuak) which usually occurs about a month before the festival itself.

2. Nutok bram tuak - pounding and preparing glutinous rice for making rice wine.

3. Ngaga raran - erecting of cooking rack. This is done in the afternoon, after completed preparing the rice wine. The gawai chief waves a cock along the varendah (ruai) to announce the time to build the cooking racks for the rice, usually at the upper landing place of the longhouse. Gendang rayah music is played three times per round in the longhouse during the construction of the rack.

4. Ngerendam beras - soaking of the glutinous rice. This is done at about 6 p.m. after the gawai chief waves a cock to announce the event accompanied by gendang rayah music played for five times per round in the house during this event.

5. Ngelulun asi - Roasting of the rice in the bamboo. This is done in the afternoon of the next day, after the gawai chief waves his cock and make announcement. He leads a group of elders carrying offerings (piring), which he placed in a special platform called duran. After placing the offerings properly, he will sit near them until all the work at this stage is finished.

6. Sabong gawai - festival cockfighting is performed at the feast chief’s platform (tanju). Several fights are conducted there and it will be continued elsewhere on nearby clearing if the participants are still enthusiastic.

7. Makai pagi - morning meal are done to initiate the beginning of the festivals and are done along the varendah (ruai) of the longhouse.

8. Ngelumpang asi - taking the rice out of the bamboo is done after the morning meal with the feast chief waving his cock making the announcement. The rice is taken out of the bamboo and placed on a large mat where it is mixed with yeast (ragi) to start the fermentation process of wine making. The rice are then placed inside large jars and its top covered with clean clothes. Gendang rayah music is played three times per round. After this, other preparations take place like making of rice flour cakes, preparing domestic livestock for the next two weeks. The festival chief also organise a group of people to collect mandatory items from the jungle or river to be used for the offerings (piring) and these are:

• Pisang Jait (wild banana fruit);

• Engkudu and trong fruits;

• Lengki palm leaves and its shoot;

• Banjang palm leaves and its shoot;

• Batak shoots, flowers of buot, tepus, engkenyang and others planted on the padi field; and

• Smoked gerama crabs, kusing bats and fish with white scales.

9. Ngambi Ngabang - sending out invitations is done after materials of the offerings above are ready. A meeting is held by the gawai chief to confirm the number of longhouse to be invited. Four trusted men are sent out to send the invitation carrying a number of strings with knots (temuku tali), where each knot represent a day before the guest are to attend the feast. The guest untie one knot every day to remind them of the feast day. Meanwhile, a day before the big event, the women folks prepared the following items for the piring:

• Cook white, yellow and black glutinous rice;

• Fry penganan iri buns;

• Cook sungkui cake;

• Cook hard boiled eggs;

• Cook ketupat rice; and

• Fry popped rice (letup) and sago flour.

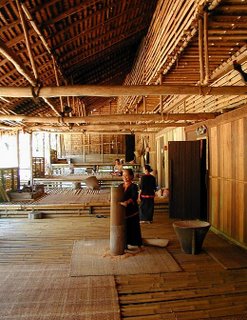

The Day of Nimang PantarThe night before the festival is known as Malam Nimang Pantar. The bards bless the raised seats (pantar) erected for honoured guest with chants. Early in the morning of this day, the gawai chief wave his cock along the varendah of the longhouse and instructed every family to build a raised seat between the varendah (ruai) and passageway (tempuan) for the guest to sit on during the feast. Gendang rayah music is played three times per round during the construction work on the raised seat. The gawai chief family is the first family to erect the raised seats followed by others afterward. After the raised seat is completed, the gawai chief again wave his cock asking each family to spread their new mats on the floors along the varendah for the Nimang Pantar event.

Muai Antu RuaCasting away the spirits of greed is done after spreading of the mats along the varendah. Two young men each drag a winnowing baskets (chapan) along the passageway, starting from the gawai chief room and going to both ends of the longhouse. As they pass each room, they shouted to the occupants to throw some unwanted articles into the basket as a material symbol of casting away all the bad luck or omen. The occupants discard their useless items and say the following words:

I present this to you, spirit of bad luck.

Take these things away to your country quickly.

The two men having received those items then toss away those items at both end of the longhouse cursing them as follows.

This is for you spirit of greed and bad luck.

Take these away to your country quickly.

These spirits are then not supposed to interfere with the festival celebration anymore.

Nyambut orang nasakWelcoming the warrior who is to prepare the offerings. When a specially invited honoured warrior arrived at the clearing of the host longhouse, the gawai chief waves his cock to announce his arrival, cleared him of the bad omen he encountered in his journey to the feast, and invited him to the longhouse as honoured guest to the feast. The warrior is asked if he encounter any bad omens on his way to the feast. If he has, then 13 glasses of tuak wine (small amount) are poured out to cool off or neutralise the power of these omens. The warrior drink six glasses, while 7 glasses are drunk by the hosts, who after this will recite a short prayer while waving his cock above the warrior’s head:

Aku miau kai manok tu,

Minta ngagai Petara,

Ngasoh kitai grai nyamai lantang senang!

Enti burong kita jai,

Manok tu ngasoh iya manah.

Enti burong kita manah,

Manok tu ngasoh iya manah agi!

I wave this cock above your head,

Praying to Goad and the spirits,

To grant us health, happiness and peace.

If your omen is bad,

This bird will make it good!

If it is good,

This cock will make it better still!

A procession is then formed, led by the feast chief who carries a flag and a man with a tray of offerings. The followed by the warrior and his followers, followed by young men beating gongs and drums. As the procession marches along the varendah, young girls and men served them rice wine. The procession covers the whole stretch of the longhouse and turned back to the feast chief apartment where the guest were seated on the raised seat erected earlier.

After the warrior guests were seated, a bard waves a cock to honour the warrior, his guidiance spirit (if any) and his followers and recites a short prayer for the well being of everybody. A special rice wine called ai aus (fluid for quenching the thirst) is served. Then they are served another round of rice wine called ai untong (individual allocated share) where the amount served varies depending on the status and age with the warrior given 18 glasses of wine and others of lesser amount. Having drunk all this ai untong, they are all served another round of rice wine called ai basu (fluid for washing or cleanse oneself) which is received from the hands of women and girls amid the war cries from the audience. They are then served with various kind of food.

Niki ka Lemambang - welcoming the bards. The bards invited to grace the festival are welcome by the feast chief and his people in a similar way as that of welcoming the warrior earlier on. If they have seen a Ketupong bird crossing their path from left to right side in their journey to the festival, the omen is called raup ketupong, and must be cooled down by offering 50 glasses of rice wine to the bards. If the happening occurs closer to the bard’s house than the hosts, the bard must drink 30 glasses out of 50 glasses, the remainder being drunk by the feast chief and his friends. If the omen occurs nearer to the hosts house, then the party of the feast chief must drink the 30 glasses and the bards drink only 20 glasses.

If the bards have met a pimpin jaloh omen, the flying of Ketupong with repeated quick calls from the right to the left side of the road, the omen must be cooled down with 70 glasses of rice wine apportioned, similar to the above, between the two parties according to where the omen occurs.

After the bards welcoming reception at the pendai (landing place), the warrior who is appointed to kill a ritual piglet (manchak babi) at the foot of the stairway entrance to the longhouse, lead the procession from the landing place. Another warrior who has been appointed as tukang nasak follows him. Tukang nasak is the warrior appointed and in charge of dividing the main sacrificial offerings of the festival. Others will not be allowed to be involved in the division of the offerings. Behind the tukang nasak walk two women, one bringing pop rice which she showers along the route of the procession, the other brings yellow rice grain which she sprinkles as they walk. The bards who start to perform the first pengap song of the gawai as they enter the longhouse follow these hosts.

The procession, similar to the welcoming of the warrior event earlier, takes a turn at the end of the longhouse and proceeds to the gawai chief varendah. There the gawai chief welcome them with the customary waving of the cock above their heads. A similar ai aus rice wine is served and followed by ai untongs. The chief bard takes 80 glasses of wine, while his assistant (saut lemambang) receives 70 glasses. The rest receives 60 glasses.

The Night Of Nimang PantarThe eve of the feast is known as Malam Nimang Pantar, where the bards bless the seats with ritual songs.

1. Ngerandang JalaiClearing a path the length of the varendah for the bards to sing along. After an evening meal is over, at about 9.00 pm, an influential man of the longhouse performs a berayah dance known as ngerandang jalai. The purpose is to clear the spiritual obstacles from the path along the whole longhouse varendah accompanied by gendang rayah music, and he traverses the varendah not more than three times.

2. NgelalauEnclosing the path already cleared. After ngerandang jalai dance is over, another important man performs the rayah dance to erect the lalau, a spiritual fence along the varendah so that the soul of the bards will not stray away as they perform. If this is the first time the people of the longhouse celebrated the Gawai Burong, the chief bard will lead his followers to perform the Ngiga Tanah Alai Berumah chants (looking for a suitable land for a house site). If the longhouse has celebrated the festival before, the lead bard will lead his followers to chant themed Ngerara Rumah (To recite why the house is made ready for a grand festival).

3. Ngading Iyang LemambangInvocations of the bard’s guardian spirits.

4. Nyerayong PandongCovering the shrine with pua kumbu.

5. Lemambang belaboh mengap niti rumahThe bards begin to sing their chants along the house varendah.

6. Beranchau TikaiSpreading of the mats.

7. Lemambang berunsut ngena ubat enda layuThe bards anoint their body with charms to prevent themselves from being cursed by anyone or spirits.

8. Ngerintai Tuai LautNaming the spiritual Malay chiefs invited to the feast.

9. Ngerintai Tuai DayakNaming of the spiritual Dayak leaders to the feast.

10. Ngerintai Tuai Orang PanggauCalling upon the spirits chiefs of Orang Panggau to the feast.

11. Ngerintai Tuai Orang GellongCalling upon the spirits chiefs of Orang Gellong to the feast.

12. Ngalu PetaraWelcoming the invited spirits to the feast. This event is a procession called ngalu Petara to the feast. It is led by the warrior who will divide the offerings (Tukang Nasak), followed by a master ceremony who will announce the purpose of the procession along the route, followed by two senior women, one carrying a plate of pop-rice which she will sprinkle along the route and another lady carrying a plate of offerings. They are followed by a band of festively dressed young men and girls from every family in the longhouse who carry rice wine. Behind them walk the musicians who play gendang panjai on the drums and gong.

As the procession goes up and down the varendah, a senior guest asks what the procession is for. The master ceremony replies that it is to welcome the invited guest from Panggau Libau, Gellong, the spirit of the Malay chiefs as well as the spirit of the iban ancestors to the feast.

The senior guest will then reply the master ceremony assuring him that the spirits mentioned has already arrived saying,

Petara amat udah datai.

Sida mai ubat serangkap genap,

mai pengaroh gembar tuboh,

ngasoh bumai bulih padi,

ngasoh bedagang menang babeli,

enggau ngasoh gerai nyamai nguan menoa.

This question and replies are repeated at every varendah of the longhouse occupant during the procession.

13. Ngiga Orang diasoh ngambi Sengalang Burong ngabangLooking for the young men to send invitation to Sengalang Burong to the feast. The chief bards and his followers started a pengap chant narrating the process of choosing able-bodied spiritual guest to invite Sengalang Burong to the feast from his home in the dome of the sky. Their narratives covers the followings:

• Bujang Lelayang seduai Bujang Kesulai Begari deka nurun ngambi ngabang - A swift bird and a butterfly dressed themselves to fetch Sengalang Burong.

• Ambai mekal seduai enggau ubat - their sweetheart equip them with charm.

• Bujang Lelayang seduai Bujang Kesulai nurun ngejang ka rumah - a swift bird and a butterfly depart the longhouse.

• Datai ba menoa bunsu ribut - arrival at the country of the God of Wind where they seek his help in sending out the invitation to Sengalang Burong Home in the sky.

• Bunsu Ribut ngambi ngabang - The God of Wind sends out the festival invitation.

At this juncture, the bards end their ritual chant for the night of the nimang pantar.

The Festival DayAt about 7.00 am early next morning, a traditional cockfight takes place on the open-air varendah or tanju of the gawai chief. This is followed by the morning meal. After the meal, a ceremony to drive away bad spirit, similar to the previous day, is conducted. Then the old head trophy or skulls in the longhouse is taken down from their respective cluster and brought to the feast chief’s varendah (ruai) in a winnowing basket, which contains the offerings.

Shortly after the skulls have been brought to the feast chief’s varendah, one man kills a chicken and smears its blood on the sacred hornbill statue (Kenyalang) at the loft (sadau) of the longhouse. As he smears it with blood, he shouted three times. Then the statue is carried down to the feast chief varendah and is placed near the skulls.

1. Nyambut Pengabang (welcoming the guest)When the invited guest arrives from their respective longhouse at the host-landing place, they are assembled and welcomed in the same manner as the warriors and the bards earlier. But the individual share of rice wine served to the Warleader, Penghulus and Tuai Rumah are different. Warleader are given 18 glasses of rice wine, Penghulus 17 and the longhouse headmen 12 glasses. Other people receive 8 or 9 glasses each.

2. Antu Pala dibai ngabang (old smoked skulls are brought to the feast)If any guests brought their old smoked skulls to the feast, as custom requires, the bard who carry them will start to sing the timang antu pala chants as they lead the procession of the guests into the longhouse and along the varendah.

3. Kenyalang Lama dibai ngabang (The old sacred statues of the Rhinoceros hornbill are brought to the feast)Descendant of past great chiefs and warleader who have kept old sacred statues of the Rhinoceros hornbill (Kenyalang) are expected to bring these with them from their longhouse to the feast. Before the statue is taken away from the loft where it is kept, a fowl must be killed and a man smears its blood on the statue whilst shouting war cries three times in succession.

The statue is then carried reverently along the path to the host longhouse. Near the longhouse, after dressing themselves at the host landing place, a bard and his team, including the host, welcome their guest similar to the previous event. A chief bard, who leads at the head of the procession, chanting their timang Kenyalang song, carries the hornbill statue. His fellow bard, who sings the chorus, follows him.

4. Ketanju lemai gawai deka nyadi (Celebration on the tanju on the eve of the feast)At about 3.00 pm of the festival day, the feast chief waves a cock along the varendah and ask his people to spread their mats on his tanju platform and two tanju next to his on both sides. The women also decorate the tanju fence or railing with a selection of their best pua kumbu (woven tie-dye blankets). A noble warrior then kills a medium-size pig (babi sengajap), whose blood is smeared on the ritual pole (the tiang chandi or the kalingkang pole for the first stage of Gawai Burong), which will be erected at the centre of the tanju. A number of leading weavers will then decorate the pole with coloured cotton balls, an event called nali kalingkang. When the pole is raised, these leading weavers will then throw eggs and balls of glutinous rice at the pole from a distance, for according to Iban beliefs, whoever hit it and stick the glutinous rice there will become expert in weaving.

Warleader, noble chiefs of the area and their senior relations are seated in places of honour close to the tanju fence. The warriors sit around the foot of the ritual pole, and others crowd around the rest of the tanju. The bard will then come out to the tanju carrying the host longhouse smoked skulls and start chanting rituals song for the skull. After finished with this, the host rhinoceros hornbill statue is brought out together with the skulls brought by the guest to the tanju accompanied by bards who will chant the ritual song (timang Kenyalang) for the hornbill statue. After finished chanting their ritual songs, the bards then place the hornbill statue and the skulls at the foot of the ritual pole.

A miring ceremony is then conducted accompanied by gendang rayah music. First, a leading warrior and six other warriors divide the offerings into seven or more plates. Then a leading warrior recites a long prayer, nyampi, to summon Sengalang Burong and his associates to come down from heaven and join the celebration.

5. Berayah Ngelingi Pun Sabang (Dancing around the foot of cordyline plants)After the miring ceremony, gendang rayah music is again played. At the same time, ketebong drums are beaten and steel adzes resound; this music called gendang pampat to call Sengalang Burong and his followers to come down from the sky. With repeated war cries, a band of warriors performed the war dance (ngajat rayah) around the cordyline fronds at the foot of the ritual pole (tiang chandi).

6. Antu Pala enggau Kenyalang dibai lemambang pulai ari tanju (The skulls and the hornbill statue are brought back by the bards from the open varendah to the longhouse varendah (ruai)As the ceremony on the tanju ends, the skulls are brought to the ruai and placed in the winnowing basket with one bard left to look after the skull while the other bards enter the family room starting with the gawai chief’s own room, chanting their ritual songs called mupu ka antu pala (collections for the skulls).

As they bless each family with ritual songs from room to room, the bards are rewarded by senior lady representative of each room with rice wines, penganan buns, gold, silver, brass rings or money, which they bring back with them.

7. Kenyalang dibai Lemambang pulai ari tanju (The hornbill statue is brought by the bard from the open varendah)The hornbill statue are brought back by the bard to the ruai and placed near the skulls. Their ritual songs accompany this and thus end the event at the tanju.

8. Makai lemai (dinner)After all the guests have returned from the tanju to the ruai, they are served supper.

9. Nyugu babi (combing the sacrificial pig’s hair)After the supper, the feast chief waves a cock and announces that the nyugu babi procession is to take place. A senior man of the host longhouse is selected to carry a flag and leads the procession, followed by a second senior man carrying a spear for stabbing the pig and followed by the third man carrying a plate to be used for carrying the pig’s liver. Two influential ladies follow them carrying popped and coloured rice, the second, a brass container filled with water and a comb. They are followed by a group of maidens in traditional festive attire, who are followed by young men in full festive attire adorning ceremonial swords decorated with hornbill feathers and head dresses decorated with local pheasant bird (burong ruai) feather. Gendang panjai music is played as the procession marched around the whole length of the longhouse varendah three times. This procession ends at the feast chief tanju where the first influential lady throws the popped and coloured rice to the air whilst beseeching favourable omen, luck, fortune and well being from the pig liver. The second women then pour the water on each pig and comb its hair as she prays along. This done, the procession disperses and the guest are seated again on the gawai chief’s tanju to listen to the evening chants by the bards.

Before the bard could start singing their chant, the warriors performed the ngerandang jalai, ngelalau and Berayah pupu buah rumah ceremony similar to the event at the start of the gawai eve. As soon as the warrior’s event is finished, the bards start to perform their gawai chants, which is a continuation of the first evening chants. This time the narratives (pengap) started with the God of Wind arrival, which scared off the slave of Sengalang Burong, Bujang Pedang, due to its awesome noise and might as he blows its way into their country in the dome of the sky.

The sequences of events in the narratives (pengap) by the bards are as follows:

• Bujang Pedang ninga auh ribut lalu rari (Bujang Pedang hears the sound of a mighty wind and runs away)

• Bini Sengalang Burong chelap bulu (Sengalang Burong’s wife is chilled by the wind)

• Ribut mangka ka rumah Sengalang Burong (the wind blows hard on Sengalang Burong longhouse)

• Ngiga kayu rumbang tutong (looking for hollow wood for the drum)

• Sida Ketupong Mansang ngayau (Ketupong and his friends go to war looking for fresh head to be brought to the human feast)

• Menoa Besi Api (The land of the flint)

• Menoa Tuchok (The land Tuchok lizard)

• Menoa Sandah (The land of Sandah)

• Menoa Rioh (The land of Rioh insect)

• Menoa Nendak (The land of Nendak bird, white rumped shama)

• Menoa Beragai Samatai Manang Burong (The land of Beragai bird)

• Menoa Kelabu Papau Nyenabong (The land of Kelabu Papau bird)

• Menoa Pangkas tauka Kutok (The land of Pangkas bird or Kutok)

• Menoa Bejampong (The land of Bejampong bird)

• Menoa Embuas (The land of Embuas bird)

• Menoa Ketupong (The land of Ketupong bird)

• Menoa Kunding Burong Malam (The land of Kunding)

• Menoa Rintong Langit Pengulor Bulan

• Bala Ketupong nyurong lalu ngaga langkau kayau (Ketupong and his warriors erect the war hut)

• Ketupong enggau Beragai matak bala (Ketupong and Beragai led their warriors to war)

• Bala Ketupong nuntong ba rumah Beduru (Nising) (Ketupong’s troop landed at Beduru’s longhouse)

• Wa Puji (Songs of praise)

• Wa Empas (Songs of anger)

• Pulai Ngabas (Return from spying)

• Sengalang Burong nusoi mimpi diri (Sengalang Burong relates his dream)

• Mimpi Ketupong (Ketupong relates his dream)

• Mimpi Beragai (Beragai relates his dream)

• Bala Ketupong ngerampas (Ketupong’s troop start to attack)

• Datai ba tinting pangka sealing pulai nyerang (Arrive at the ridge where the warriors shout victoriously on return from battle)

• Bini Sengalang Burong nyambut igi balang (Sengalang Burong’s wife receives the precious skull)

• Aki Lang Sengalang Burong mai ngabang (Sengalang Burong leads his people to attend the festival)

• Mansa Tembawai Lama Sengalang Burong (passing the old house site of Sengalang Burong)

• Menoa Bujang Jegalang (The land of Bujang Jegalang)

• Mansa Batu Ansah (Passing the whetstone)

• Mansa pun buloh berani (passing the foot of Buloh Berani)

• Pintu Langit (Arrival at the door of the sky)

• Bala Sengalang Burong ngetu ba pintu langit ke rapit (Sengalang Burong and his followers stops at the closed door of the sky)

• Menoa Aki Ungkok (The country of Aki Ungkok)

• Menalan Sabong (The cockfighting ring)

• Ngerara rampa menoa (Appreciating the view of the landscape)

• Menoa Raja Siba Iba (Raja Siba Iba’s country)

• Menoa Burong Raya (The country of Burong Raya bird)

• Menoa Sera Gindi (The country of Sera Gindi)

• Menoa Bengkong apai Kuang Kapong (the country of Bengkong, father of Kuang Kapong bird)

• Menalan Besai (a widely cleared space)

• Menoa Bhiku Bunsu Petara (The country of high priest of the god)

• Menoa Selampandai (The country of Selampandai)

• Menoa Raja Rengayong Kijang (The country of Raja Rengayong the barking deer)

• Menoa Rusa Bunji (The country of sambar deer)

• Menoa Raja Remaung (The country of the tiger chief)

• Kendi Aji (The road junction)

• Kampong Baung (The lonely forest)

• Menoa Aki Dunju (The country of Aki Dunju)

• Menoa Durong Biak (The country of the younger Durong)

• Menoa Bunsu Petara (The country of Bunsu Petara)

• Menoa Bangkong (The landing place)

• Bala Sengalang Burong mandi (Sengalang Burong and his followers bathes)

• Bini Sengalang Burong mandi (Sengalang Burong’s wife bathes)

• Bala Sengalang Burong begari (Sengalang Burong and his followers dressed up for the festival)

• Bala Indu besanggol (The women plait their hair into buns)

• Bala Sengalang Burong niki ka rumah (Sengalang Burong and his followers walks into the feasting house)

10. Ngalu ka Sengalang Burong (Welcoming Sengalang Burong)This event is done early in the morning with the gawai chief waving his cock announcing the arrival of Sengalang Burong. A procession is held heralding the arrival of Sengalang Burong and his followers. The gawai chief is leading the procession followed by another man who wave a cock to honour both the visible and invisible (spiritual) guests. After him walks two influential women, one carrying a plateful of pop rice and another, a plate of offerings. Behind them walk the girls and young men who wear traditional dress. The girls carry empty wine glasses, and the young men have a bottle of rice wine each. At the end of the procession walks a band of young men who play music on drums and gongs.

After they circled the longhouse varendah three times, and have reached the gawai chief’s varendah, they stopped and sit down facing the honoured warriors and guests and served them as a symbolic serving of the Sengalang Burong, his followers and other invited spirits. The host, in this instance, are represented by our spiritual heroes of Panggau, Keling and Laja, who will entertain Sengalang Burong himself, and is narrated in the pengap chant of the bards.

11. Lemambang Nenjang Sengalang Burong (The bards sing a song in praise of Sengalang Burong)In this event, the bards faced the most honoured guest, who is sitting together with other important guest along the upper varendah (Ruai atas). This honoured guest is now representing Sengalang Burong while the others represents his son-in-laws and other followers.

After this, the night’s chants of the bards are concluded. Another nyugu babi procession is held at about 6.30 am and the pigs are sacrificed, their liver being divined by the experts. A morning meal is also served again.

End Of The Festival1. Miau ka manok kena Ketanjuwaving of the cock to announce the ceremony at the open varendah. The gawai chief waves a cock and announces the second event on the open varendah is about to happen, as on the previous day and invited every guest to gather at the tanju.

2. Miring Dividing the offerings. This is performed by the warrior groups who prepare seven offerings on seven trays at the tanju. When finished, it is covered using the best pua kumbu blankets placed carefully over it. These offerings are placed at the foot of the ritual pole, and some of the offerings are hung at each end of the longhouse roof. While miring is going on, the bards once more bring the skull and the hornbill statue to the tanju accompanied by their ritual song called timang antu pala and timang Kenyalang respectively, same as what was done on the previous day.

After the skull has been placed on the winnowing basket (chapan) and the hornbill statue placed closed to the skulls, gendang rayah music is played, while the leading warriors (raja berani) performed the ngerandang jalai dance circling the tanju three times to clear the space off the evil spirits. Then followed by a rayah dance performed by ordinary warrior (bujang berani) known as ngelalau, also circling the tanju three times. This serves to fence the path already cleared by the raja berani warriors earlier. Shortly after ngelalau dance, older men representing each longhouse invited to the gawai, perform another dance, which is called Berayah Pupu Buah Rumah. They encircle the tanju three times as was previously done.

After the dances are over, one of the most influential war leaders recites a long sampi or prayer, inviting Sengalang Burong and his followers to come down from haven to attend the feast. As he recites this prayer, gendang pampat music is played. Another man beats an iron adze (bendai) inviting the spirits including the spiritual war heroes from Panggau Libau and Gellong world to join the feast. The invited guest like the warleader, hereditary chiefs and community elders has been seated in their respective place of honour during this part of the ceremony.

In this event, the warriors eat raw or half-roasted chicken and pork meat at the foot of the ritual pole. This is done to encourage the invited spirits, who are believed to have come to do likewise, as a show of fearlessness, bravery or courage especially among the warrior groups. Food and rice wine are continuously served throughout this event. Fearsome war cries can be heard frequently as the event climaxed.

Eventually, as the ceremony comes to an end, the bards carried the smoked skulls and the sacred hornbill statue inside the longhouse again. The statue is brought by the bard into individual family room to bless each family as they chant their ritual timang Kenyalang song. The bard, who bears the skull, will leave the skull at the Gawai Chief varendah (ruai) inside a winnowing basket and they themselves (without the skull) will enter individual family room chanting the timang antu pala songs.

While other bards performed the timang Kenyalang and timang antu pala chant at individual family room, another bard who sang the Gawai Burong festival songs (pengap) during the previous night, start to bless one woman from each family. These women have been gathered and seated in line on the pantar of the Gawai chief varendah (ruai). This event is called Denjang Indu (the blessings of the women). The songs may be repeated many times, as they need to bless these women representatives individually and may take considerable time.

3. Ngamboh Forging war knives for the gawai host. Following the bedenjang ceremony, the bards chant another song to symbolises forging (ngamboh) of the war knives for the host. Other chants including ngiga tanah (to look for suitable farming land) to symbolise the blessing for good farming years to come. The final chant by the bards would be the mulai ka samengat (sending back the spirits and the souls) to the Peak of Rabong Mountain, the domain of the spirit and souls of the bards and shamans.

After the bards have finished chanting their ritual songs, the feast chief waves a cock along the varendah to announce that the feast has ended. Their respective owners have returned all skulls presented during the festival to their former places, and the hornbill statue returned to their honourable place at their owner’s loft for reuse in future.

After the conclusion of the ceremony, the people of the host longhouse will avoid normal work for seven days. Gendang rayah music is played every day before sunset to invite universal spirits to visit the house and give their blessings during these seven-day periods.

At the end of seventh day, the ritual-offering pole (tiang chandi or kalingkang) is dismantled and the cordyline palm (sabang) is planted on the upriver side of the house as a mark of respect to commemorate the festival just completed.

Ahhh nadai ko enggau meh baka Christmas ke taun tuk, ka pan enggai ngintu ba tempat kerja aja meh. Nadai nemu daya endang sigi udah gaya pengawa. Ngarap ke Petara semampai meri berkat Iya ngagai kitai semua lalu semampai bisi begulai enggau kitai enda milih dini alai. Sama-sama meh kitai meri terima kasih ngagai Iya ketegal ke udah merkat pengidup kitai sepanjai taun 2006

Ahhh nadai ko enggau meh baka Christmas ke taun tuk, ka pan enggai ngintu ba tempat kerja aja meh. Nadai nemu daya endang sigi udah gaya pengawa. Ngarap ke Petara semampai meri berkat Iya ngagai kitai semua lalu semampai bisi begulai enggau kitai enda milih dini alai. Sama-sama meh kitai meri terima kasih ngagai Iya ketegal ke udah merkat pengidup kitai sepanjai taun 2006 Enggau peluang tuk, aku meri Selamat Hari Christmas 2006 serta Selamat Nyambut Taun Baru 2007 ngagai semua ka bisi lalu kitu. Ngajih ke kitai semampai bulih pengerai serta mujur dalam semua pengawa lalu bulih pengelantang ba pengidup dalam taun ti ka datai.

Enggau peluang tuk, aku meri Selamat Hari Christmas 2006 serta Selamat Nyambut Taun Baru 2007 ngagai semua ka bisi lalu kitu. Ngajih ke kitai semampai bulih pengerai serta mujur dalam semua pengawa lalu bulih pengelantang ba pengidup dalam taun ti ka datai.